NE NEWS SERVICE

TOKYO, OCT 23

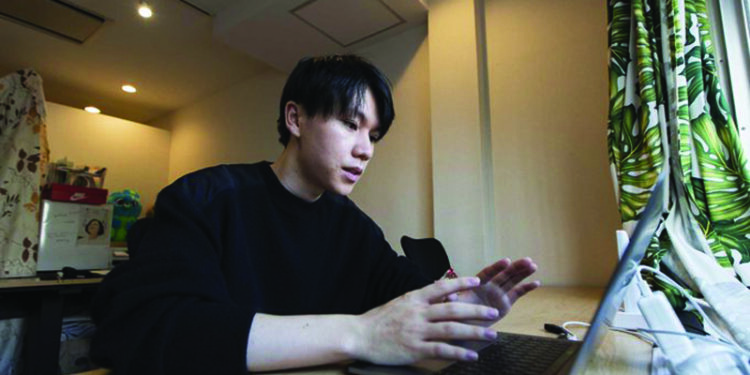

Suicides are on the rise among Japanese teens and that worries 21-year-old Koki Ozora, who grew up depressed and lonely.

His nonprofit “Anata no Ibasho,” or “A Place for You,” is run entirely by volunteers. It offers a 24-hour text-messaging service for those seeking a sympathetic ear, promising to answer every request — within five seconds for urgent ones.

The online Japanese-language chat service has grown since March to 500 volunteers, many living abroad in different time zones to provide counseling during those hours when the need for suicide prevention runs highest, between 10 p.m. and the break of dawn.

What makes Ozora”s idea work during the pandemic is that it”s all virtual, including training for volunteers. Online volunteer services are rare in Japan.

“This really gives me hope,” Ozora said of the flood of volunteers. “They tell me they just had to do something.” A Keio University student, Ozora designed the site setup, which allows more experienced staff to supervise the counseling. Anonymity is protected.

Anata no Ibasho has received more than 15,000 online messages asking for help, or about 130 a day.

The most common ones are about suicide, at about 32%, while 12% deal with stress over raising children. The goal is to offer a solution within 40 minutes, including referrals to shelters and police.

The messages speak of deep pain. They confess to fears about killing own children. Another talks about self-hate after being sexually abused by a parent.

Contrary to the stereotype of Japan as harmonious, families are increasingly splintered. A recent OECD study found Japan ranks among the highest in the world in suffering isolation, when measuring the contact individuals have with other people.

Japan has about 50 suicides a day, a woman is killed once every three days by her partner or former partner, and 160,000 cases of child abuse get reported a year, according to government and U.N. data. Several celebrities” deaths by suicide this year have raised alarm.

Counseling through online chats can be a challenge, because all you have are words, said Sumie Uehara, a counselor who volunteers at Anata no Ibasho. People tend to blame themselves, stuck in a negative spiral, unable to sort out their emotions, said Uehara.

“You don”t ever negate their feelings or try to solve everything in a hurry. You”re just there to listen, and understand,” she said.

Ozora feels Japan still hasn”t fully grasped the difference between a healthy sense of solitude and loneliness, which can get desperate.

His high school teacher was the first adult he could trust.

“Without him, I wouldn”t even be around today. It was a miracle I came across him,” said Ozora, adding he wants to offer that miracle to others.

Takashi Fujii, the teacher, noticed Ozora never laughed. He tried to tell him he cared and get him excited about things in life, anything, Fujii recalled.

Ozora has begun compiling data from Anata no Ibasho for a research project. He hopes to pursue graduate studies in the U.K., a world leader in tackling the public health issue, with a minister for loneliness since 2018.

But his biggest dream is to have a happy family.

“I never had that,” he said.

“There is a father, and there is a mother. The children are happy and can do whatever they want. It”s an everyday family. But, if anything, that is what I want the most.” Courtesy: AP