- Lullabies (Halardu: Gujarati), the first traditional lore available to children in the precolonial era, densely pack female cathartic and subversive energies. These cradle songs are as much for and about the mothers as they are for and about children: Prof Diti Vyas

NE EDUCATION BUREAU

GANDHINAGAR, APRIL 4

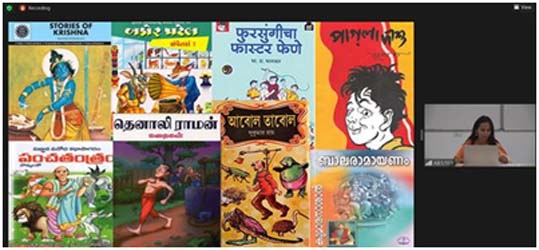

Bringing a crucial yet less talked about aspect of Indian literature to the centre, the Indian Institute of Technology Gandhinagar (IITGN) hosted two lectures that delved deeper into the variety and plurality of children’s literature in Indian languages in the precolonial era on Thursday and Friday, respectively.

The two lectures titled – ‘Between Impossibility and Possibility: Precolonial Children’s Literature in Indian Languages’ and ‘Female Voices in Children’s Literature in Gujarati’ – were delivered by Prof Diti Vyas as a part of the Institute’s Indian Knowledge Systems (IKS) elective course lecture series.

Highlighting the saliency of Indian children’s literature, in her first lecture Prof Diti Vyas said, “Indian children’s literature, developed within the boundaries of formal education after emerging as an independent body of writing, witnessed creativity, originality, and modernity in its works.” The history of children’s literature in different Indian languages is said to have started in the 19th century with the arrival of the British missionaries and the beginning of commercial printing.

However, using examples like Panchatantra dating to about 200 BCE, Prof Vyas argued, “The whole body of highly organised writing for children in the precolonial era was either ignored or touched upon as a mere predecessor with no real value, and was severely criticised.” The intricate notions of double address (addressing the child and adult simultaneously) and constructive child (signifying that young people construct their own identity out of what is culturally available rather than being passive recipients) were prevalent in precolonial Indian children’s literature. Moreover, these texts posed questions, demanding scrutiny by children rather than providing readymade answers on a plate.

The second talk by Prof Vyas threw light on how the female characters in children’s literature of Indian regional languages were seen as stereotypical due to their adherence to the traditional roles of a daughter, mother, wife, and sister; typically characterised by dependence and passivity.

Being a fundamental part of children’s literature, lullabies leave a substantial impact on the child’s psyche. Elaborating on this, Prof Vyas said, “Lullabies (Halardu: Gujarati), the first traditional lore available to children in the precolonial era, densely pack female cathartic and subversive energies. These cradle songs are as much for and about the mothers as they are for and about children.”

Their orality gave mothers the power to improvise lullabies according to their requirements, expressing various moods and emotions. However, the transition to digital streaming platforms silenced feminist revisionary attempts, causing the mother’s voice to become a monotone. Prof Vyas also read out and explained some examples of lullabies in Gujarati. Both the talks concluded with lively Q/A sessions.